Survey fatigue: Are we plundering people’s finite resources of patience and trust?

A few years ago I was asked by my bank to complete a five-minute online survey following a two-minute transaction. I got in touch with the bank through their social media chat, and suggested that perhaps this was overkill. They suggested in a friendly way that perhaps I should ignore the survey. As a researcher I suggested that perhaps their practice was undermining the value of surveys as a research tool.

They thanked me for my feedback.

So this brief moment in time got me wondering about the regular requests for feedback surveys that we receive. I then monitored the number of survey requests that I received between Halloween and Christmas, and it transpired I was being asked almost every two days to take part in some sort of survey. That was back in 2017. In 2020 I repeated the monitoring over the same period and found it had increased to exactly every two days.

These were all online surveys, which are cheap and easy to run, and can be set up by anyone with access to the internet. It made me wonder if the sheer frequency of surveys that we receive may actually be undermining my practice as a researcher – as someone who regularly employs online surveys in my own work.

I turned to the concept of the tragedy of the commons. The concept has been around for some time but gained traction in the 1960s by Garret Hardin, a biologist writing about the challenges of over population, and looking at resources that were held in common like grazing land or fish stocks. At its essence Hardin was arguing that if one person finds a fishery they’re able to fish and return a living. But as more people find that fishery and exploit that fishery the stocks decline, and ultimately their living is ruined. So the tragedy of this is that each individual is acting rationally in their own interests and they’re locked into a system of exploitation without limit, based on an assumption that this is an infinite resource. But ultimately it destroys that which is held in common and destroys their own livelihood. One only has to look at our Southern Ocean, where orange roughy fish stocks were depleted near to exhaustion to see this is not a historical issue but a constant challenge.

As Hardin himself said:

…the oceans of the world continue to suffer from the survival of the philosophy of the commons… Professing to believe in “the inexhaustible resources of the oceans,” they bring species after species of fish and whales closer to extinction.

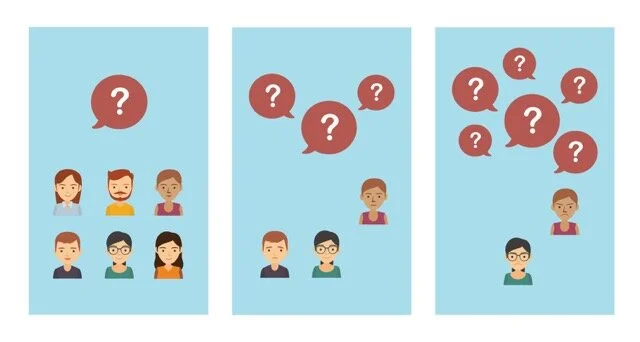

So looking to survey research, until relatively recently, this was expensive and time-consuming. We would often see researchers out on the streets literally with their clipboards, and people were asked to take people in surveys that were fairly well-controlled because of the pressures of time and cost and quality. But as the illustration below suggests, as the cost of surveys have declined rapidly with the advent of online survey tools, the potential reach of surveys has grown exponentially. But I would argue that survey participation relies on a certain level of goodwill, and I wonder if as with other goods held in common, are we treating goodwill as an infinite source, when in fact goodwill has a breaking point? Are we as researchers, similarly locked into a system of exploitation that will ultimately be to our ruin?

There is a body of evidence to show that survey fatigue is real, and is driven by a range of factors, including over-repetition of themes, length of surveys, over-surveying, and spatial bias (where some areas for various reasons get over-researched – marginal electorates for example).

And the research industry itself has guidance for reducing survey fatigue, including using simple language; considering how the survey is being experienced by the participant; timing of the survey; question design and selection; communicating value of the research; and shorter surveys. But in a commentary that I recently published in Evaluation Matters, these are technical solutions, and simply ask us to do surveys differently, not to rethink our practice entirely, and fails to ask the question if we should be doing surveys at all in many circumstances.

There are also arguments to be made that a tragedy of the commons is not inevitable. Drawing on the work of Elinor Ostrom, it could be argued that with thought and care to craft rules, communities of practice, and institutions, a commons can be sustained, including the commons of people’s goodwill and trust.

In our own professional practice, we can give think about when we need to make use of surveys by critically linking criteria to data collection. We need to collect data based on what we value, rather than valuing simply what we can conveniently collect. As someone who has been working in active transport, I know that we’ll be solving the problem of why so few children cycle to school when we see more bikes in bike racks around the country. Often, we can draw on existing data sources rather than necessarily seek new ones.

We can also build capability to make good data-gathering decisions. It is not enough to train people in such tools as online surveys; we need to frame the training with a discussion of how to design research, and how to identify the data we need to answer our research questions appropriately.

In our professional networks and institutions, we can foster good practice and a commitment to delivering fit-for-purpose research and evaluation.

Perhaps most importantly, we need to reciprocate. It’s not enough to deliver a report to a client, and all too often those who gave their time, thoughts and experiences are left behind. A simple summary of research findings, how they’re being used, and the value they offered, given back to those who participated, can be a huge sign of goodwill.

Now perhaps people don’t mind all that much about taking part in surveys, and levels of goodwill remain strong. But even if that is one day borne out, we still need to continually strengthen our practice, challenge poor research design, and reciprocate the generosity that research participants show in welcoming us into their lives. But if in fact trust in our profession is being eroded, I would argue we need to further strengthen our practice and challenge the values that erode that trust.

The Evaluation Matters article that this is based on can be accessed here. My thanks to Emily Garden for the illustration above.

References

Field A. 2020. Survey fatigue and the tragedy of the commons: Are we undermining our evaluation practice? Evaluation Matters—He Take Tō Te Aromatawai. 6: 2020

Hardin G. 1968. The tragedy of the commons. Science. 162 (3859): 1243-1248.

Ostrom E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.