Getting a nudge: Moving from niche innovations to systems change

The bread and butter of many evaluators is to look at innovative pilots or prototypes, explore how they were developed and implemented, and in different ways assess their impact and overall value. Yet all too often, no matter how exciting the innovation, how successful it is in having a local impact, and how much value it creates, systems can be remarkably unresponsive to scaling pilots more widely. The pace of uptake is often slow or non-existent, with the consequences that benefits are spread unevenly, and the complex problems the innovations were looking to address remain embedded.

Working with colleagues from Kinnect Group, we had the privilege of following four innovative road safety projects working under the banner of the Signature Programme, led by ACC and the New Zealand Transport Agency. Each project was intended to trial innovative ways of working, and if successful, influence road safety policy and systems nationally.

With a three-year frame to work within, we had the luxury of being able to follow the projects to explore the outcomes they were achieving, and to develop an understanding of how the projects were able to nudge business as usual activity in road safety.

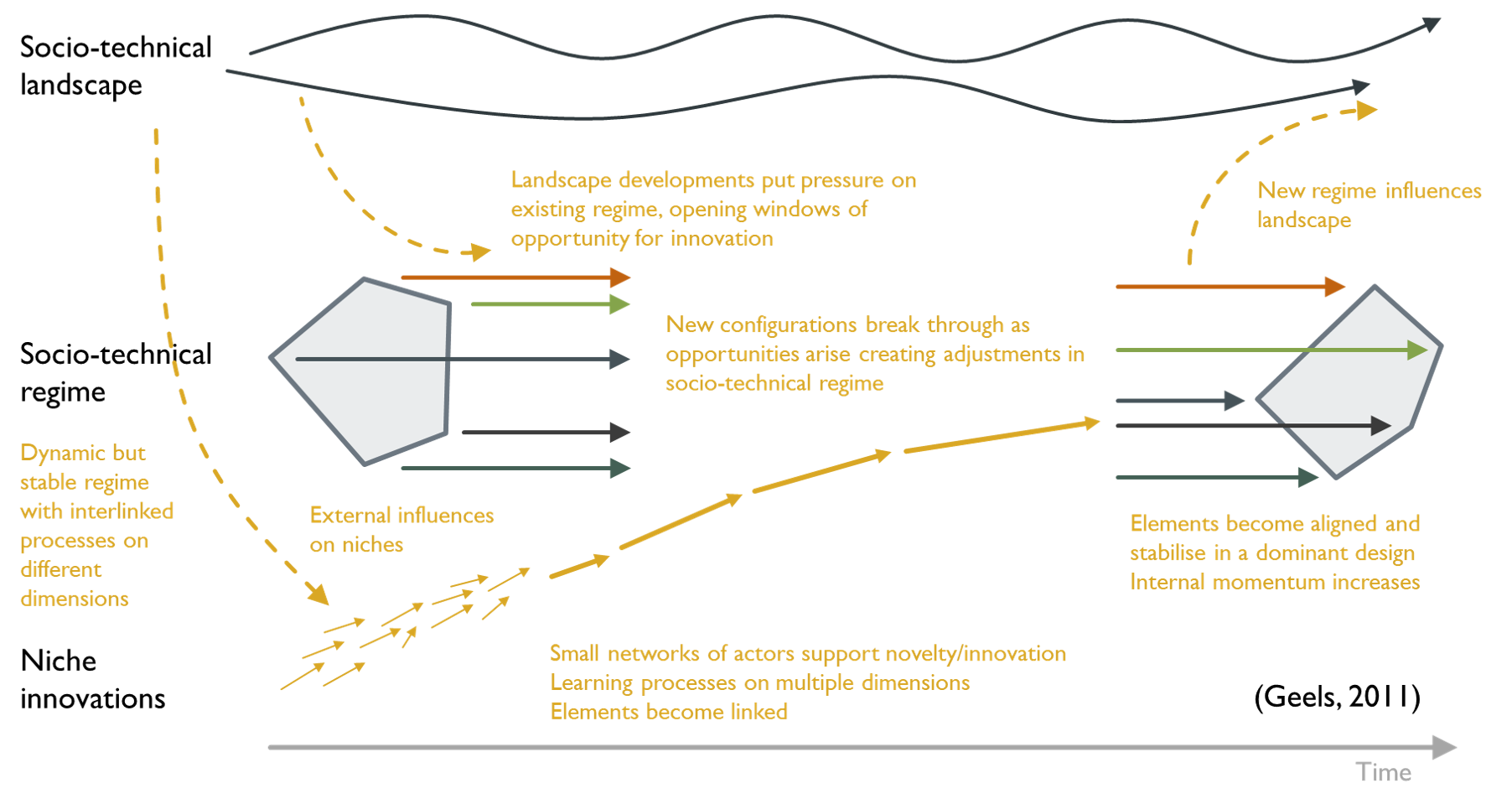

As we followed the trajectory of each project, socio-technical systems theory became a key reference point for us. This frame of thinking explores how niche innovations progress to become embedded as business as usual within systems and organisations.

Developed by Frank Geels, a ‘socio-technical transition’ is one where social and technological forces come together to create major shifts in transport, energy and other systems (see the reference to Geels 2011 below). Geels posits that socio-technical systems have three key elements:

Systems that include supply side (innovation) and demand-side (user environment)

Actors that are involved in maintaining and changing the system; they carry, reproduce and challenge the rules in their activities

Rules and institutions that guide actor’s perceptions and activities; they provide constraining and enabling contexts for actors and systems

Interaction of elements in a socio-technical regime

Put briefly, socio-technical systems theory proposes that the combination of rules that are regulative (explicit and formal), normative (values, expectations, rights and responsibilities) or cognitive (the frames through which meaning or sense is made), together act within social technical regimes that are interlinked and maintain the stability of a system. These regimes combine socio-cultural, policy, science, technological and market forces that together can be very effective in resisting the pressures of change.

The diagram below shows the process through which socio-technical transitions are theorised to occur, or which may be prevented from occurring through the interrelationship of rules that govern systems. There are three levels of interplay:

Niches: the locus for radical innovation; these are often protected spaces where innovation is permitted to operate and even flourish.

Socio-technical regimes: the ‘deep structure’ of established rules and systems that stabilise current practice, and are shaped by technological, scientific, policy, socio-cultural and market forces.

Socio-technical landscape: the wider context that influences niche and regime dynamics, including trends, values, ideologies and macro-economic patterns (Geels 2011).

Socio-technical transitions from niche innovations to systemic change

For a niche innovation to become sufficiently embedded to ‘nudge’ changes in systems, a combination of factors is needed that can work at macro (national/international); meso (city); and micro (community) levels (see Marletto 2014). This is a non-linear process involving a complex interplay of different factors. New innovations must break through to the socio-technical regime as opportunities arise, creating adjustments, stabilising and eventually establishing themselves as the new regime, in turn influencing or shifting the socio-technical landscape.

A socio-technical approach proposes that in many cases, the technical solutions to complex problems already exist; what matters is having the organisational structures and system processes that enable their proper use. This approach signals a shift in focus towards relationships rather than actors, on actions rather than functions. But such shifts are hugely challenging because there are many ways in which the actors within a dominant system work to preserve their position – as anyone trying to nudge the dominant position of the car in transport systems has found (see for example Cohen, 2012).

In the discussion that follows, we’ll look at two examples from the Signature Project and the extent to which they were able to bring about systemic change.

The first example was Behind the Wheel, an innovative driver licensing project, aimed at improving the driver licensing journey at a local level and improve safety outcomes for young drivers. Although itself a highly planned, well-developed and system-focused local intervention, it was also one of a large number of community-based drivers licensing projects in New Zealand, limiting its potential individual impact.

More fundamentally, at a national level, the drivers’ licensing system is highly constrained, with key aspects such as driver instruction skills, costs and payment systems, and test content and processes tightly set within a range of rules and regulations that prevent rapid change. The project’s greatest immediate influence was in the changes to the licensing environment locally, and its direct feed into the national licensing resources.

The figure below details the genesis of the project, and its influence on licensing systems from a socio-technical systems perspective:

At a landscape level, the road toll, the perceived needs of employers and demands for driver licensing programme together drive demand for community initiatives.

At the niche innovation level, the project was able to implement comprehensive changes to driver licensing across the pathway of pre-learner to fully licensed.

At the system/regime level, the project directly influenced resource development, but other elements that influence licensing uptake (such as school curriculum, instruction skills requirements, costs and payment systems, and test processes) have remained unchanged through regulatory and rule constraints. The initiative does however provide learning to inform wider practice, and potentially system changes.

It is worth noting that while the national licensing system has been resistant to change, should any of the current national level activity mentioned above result in regulatory changes, these are likely to become well-embedded and have long-lasting impacts.

Influences of community driver licensing project on national licensing systems

The second initiative was a road safety programme targeting visitors to New Zealand. The Visiting Drivers project drew on the efforts of many organisations to support the safety and experience of visitors to New Zealand across the spectrum of travel to New Zealand, including planning and booking, in-flight information, on arrival information, and journey support.

A detailed evaluation report sets out the achievements of the project, and the figure below provides some context from a socio-technical systems perspective.

At a landscape level, the road toll, industry concerns of negative visitor experiences, and the inherent challenges of driving in New Zealand as a visitor created a demand for a central government-led intervention in this space.

At the niche innovation level of implementation, the Visiting Drivers partnership built an integrated system of support for visitors, spanning the continuum from planning and booking travel, in flight, on arrival and support through the journey. This was achieved through a coalition of players from central government agencies, industry and local government.

At the regime level, Visiting Drivers was able to exert rapid and widespread influence among partners, including industry practice in the target regions, road infrastructure, information sharing between operators and agencies, and coordinated messaging across the partnership. Council investment was not taken up to the degree intended. There were also national level changes made, including an industry code of practice, police practice, driver information resources, and to some extent, NZTA investment criteria.

Importantly, for Visiting Drivers (and in contrast to Behind the Wheel), legislative change was not needed, and enabled rapid mobilisation of activity across partners. But this also had the effect that when resources were reprioritised, some aspects of project activity ended quickly.

Influence of Visiting Drivers project on systems

In evaluating these projects, we concluded that local niche innovations are as important for the systemic barriers and enablers that they reveal, as they are for the impacts that they have on a local community.

If we simply treat innovations as local level pilots, we lose sight of the system issues that can constrain or enable successful outcomes, and the broader system levers and changes that we need to scale local innovation. Institutions, power dynamics, incentives and politics – factors that contribute to the complexity of systems – all matter for bringing about change.

Policymakers should therefore explore where a system needs a nudge as much as whether or not a prototype should be continued or expanded.

We also found that that deviating from existing practice, even when the niche is sanctioned by the system owners, takes a lot of effort. And scaling the effort to wider practice and impact takes more than just doing more of the intervention; scaling requires a wider mandate to change existing rules and normative practice.

We’re very grateful for ACC and NZTA for funding and supporting the evaluation of the Signature Programme, and to the project leadership and teams who contributed across all aspects of the evaluation. Four reports on the Signature Programme evaluation can be accessed below of via the NZTA Innovating Streets website.

Further reading

Cabaj M. 2018. Evaluating efforts to scale social innovation. Here to There Consulting. Waterloo, Ontario.

Cohen MJ. 2012. The future of automobile society: a socio-technical transitions perspective. Technology analysis & strategic management, 24(4), 377-390.

Geels FW. 2011. The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 1: 24-40

Marletto G. 2014. Car and the city: Socio-technical transition pathways to 2030. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 87: 164–178

Opit S, Witten K. 2018. Unlocking Transport Innovation: A Sociotechnical Perspective of the Logics of Transport Planning Decision-Making within the Trial of a New Type of Pedestrian Crossing. SHORE & Whariki Research Centre, Massey University.