Literature reviews: Not taken lightly

Literature reviews are tricky beasts. They require you to absorb the breadth of thinking on a given subject, distil key themes, distinguish between information of value or irrelevance, and to synthesise into a coherent, accessible and useful report.

Make no mistake, they are often one of the most challenging assignments any researcher can undertake.

And while literature reviews can be a sometimes lonely solo undertaking, they can be even more challenging in a team setting. I have seen professional relationships put under immense stress in delivering a literature review as different ideas, approaches and priorities come into conflict.

The challenges of literature reviews are often under-appreciated, and consequently under-costed.

But for all that, literature reviews offer hugely valuable personal opportunities to immerse oneself in a new area of thinking, to engage in a process of learning and to share insight with others.

It’s just that they’re not to be taken lightly.

From time to time I’m engaged by clients or in academic work to undertake a literature review. Topics I’ve explored with colleagues have included rural and urban economic linkages, social exclusion of disabled people, and – literally – where is the world heading and how does the fitness industry fit into it?

This post came about as I was reflecting on a review that I completed with Tanya Perrott , to support the Waikato Spatial Plan, which was recently made publicly available.

The take home messages

Every report needs to leave its readers very clear on its key findings. Literature reviews are no exception, yet there are many that are frustratingly discursive, and leave the readers to make sense for themselves.

So, to practice what I preach, here’s what’s at the heart of my literature review practice:

- Get the research question, overall scope and purpose very clear.

- Set clear expectations of what can be delivered with time and budget.

- Search within the scope.

- There’s no substitute for reading.

- Use mind mapping to build a detailed framework of the review.

- Start writing as soon as possible, and steadily refine.

- Nutshell the key findings for both one’s own and the reader’s understanding

- Speak with your own voice.

- Understand and acknowledge context and limitations.

- Write clearly and directly.

What’s the question again?

One of the greatest pitfalls in any review is a poorly defined research question. Starting with one that is ill-focused or misdirected puts us on the back foot before we’ve even begun. It is so important to be very focused on the research question – and to agree upfront the fundamental issues that the review needs to explore.

This is as true for a thesis as it is for a client report; a literature review is there to ensure the reader is up to speed with the latest thinking, the strength of the evidence base, areas of controversy and areas of unknown – all related to the topic at hand.

Part of this is understanding who the audience is for the review, and the purposes for which it will be used. Think about what are people wanting the review for, and how to craft it with that in mind.

I have learned the hard way that it’s critical to meet with the client to discuss and agree the scope, and what can be delivered within the time and resources.

How much is enough?

This is a little bit like the scope question. Expectations of the breadth and depth of a literature review vary widely. Agreeing the scope, depth and scale of the literature review early in the process is crucial.

Most of my literature analysis tends to be delivering what I call ‘rapid reviews’, where a broad range of literature is sourced and reviewed; usually there’s not the time nor the budget to explore every tract in existence on the subject. These still require careful judgement and clear criteria of what is suitable for inclusion.

These contrast particularly with systematic reviews, which aim to provide a complete and exhaustive summary of current literature. They’re used widely in health sciences as well as other fields. And they’re a significant undertaking (see for example the Campbell Collaboration and the Cochrane Library)

The search is on

Once the focus and scope is agreed, it’s time to start searching – within the scope.

There are many databases that can be used for literature searching. Scopus is widely used, but is fee-based. Google Scholar is a useful source for accessing the established thinking, but less so new and emerging thinking.

Search engines like Google are also important for accessing what’s called the ‘grey literature’, which includes reports that organisations and agencies have commissioned, but which have not been published as academic journal articles. These often provide valuable resources, particularly in the evaluation sphere.

It’s also useful to see what the client can offer in terms of in-house resources to support the search.

I find it useful to collate a first run of documents, and begin reading these, to build knowledge in the area and help refine the focus. This is always in the expectation that this reading list will grow further.

There’s no substitute for reading

I have had people on many occasions point me towards different types of software that they swear make literature analysis easier. I’ve yet to find one that is better than reading it yourself.

There really is no avoiding reading, but it’s possible to do that without getting bogged down. My approach in the early analysis phases, is to read enough to capture the themes, and to understand the limitations, and then move on.

How much reading you do is a matter of judgement. But peer review along the way (not just at the end) from colleagues or advisors can be really helpful for testing how sufficient the breadth of reading is, and further down the track, the strength of the analysis.

Mindmaps are your friend

I can’t stress enough how valuable mindmaps are in literature reviews. I would go so far as to say mindmaps are your best friend in a literature review.

Mind mapping is simply laying out on a page the themes that are coming through in the reading you’re doing.

Some people use whiteboards, some use flipcharts, but for me, digital versions like freemind and Xmind are essential. They allow me to arrange, move, rearrange and essentially create the overall structure of the literature review.

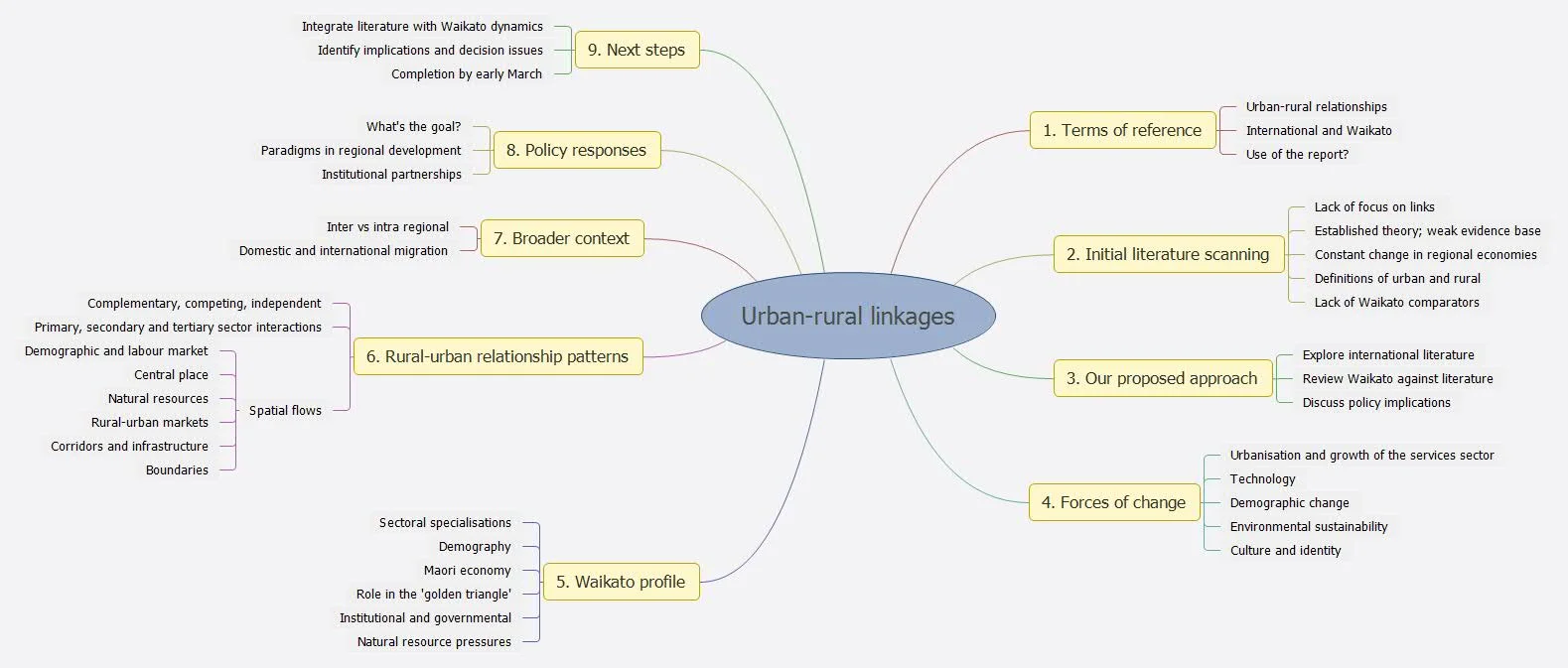

Pictured below is a mindmap that we used for the urban and rural economies review. This was a summarised version that we presented to the clients, to show the areas we were exploring, the emerging themes and the overall structure of the report.

Our client was able to see the direction we were heading in, offer suggestions for further exploration, and take in on one page the overall content.

“Don’t get it right, get it written”

Reading and learning is the fun part. Writing is the necessary next step. My approach is to start writing as soon as possible. I always have to steel myself to begin writing, but it’s just so important to get started.

That seemingly all-important opening sentence is a mirage. We can all waste precious hours chasing it.

One of the best pieces of advice I’ve been given was “don’t get it right, get it written – then get it right!” That is to say, start writing, and steadily refine and build the overall meaning and messages as the review develops.

Nutshell the findings

Nutshelling is the process of developing a distilled summary or synopsis of the key findings that are emerging. I was taught this during my graduate study, as a way of focusing thoughts and making sense of what I’m taking aboard through the review process.

For me, it’s key to building the core narrative of the review.

Nutshelling also marks the transition from being a listener of other people, to a speaker in one’s own right. It takes time, but that investment pays off in the clarity of the findings.

It involves making one’s own judgements about what answers the research question that we’re exploring, and placing the research focus at the centre of the review.

A key challenge is to avoid parrotting other people’s writing, and it’s all too obvious when that happens. Ultimately, the literature review is a process through which one’s own voice emerges as a participant in the research and overall debate.

Context is everything

Any good evaluator will tell you that everything is context dependent. What is a success in one context may very well fail under other circumstances. This is all to say be very cautious about what can be generalised, and make clear the limitations of the available research.

Clarity matters

I just have to finish with this. There’s something about literature reviews that some people seem to think gives them licence to write discursively and often impenetrably. No, you can’t.

Punctuation is there to contain one thought, and only one thought. Be tight and direct. People will thank you for it.

With thanks to Barbara Grant who, in the early stages of my doctoral study, critically shaped my own approaches to literature reviews.

… and no, I don’t have shares in either freemind or Xmind!